A walk through Kochi (Kerala, India)

A

walk through Kochi (Kerala, India)

Authors: Roman Ville-Glasauer & Bella Ullas

In this experimental walk, we are trying to demonstrate what are the main constraints that pedestrians face in Kochi (Kerala, India) and what kind of infrastructures are proposed to help their progression on the city’s streets.

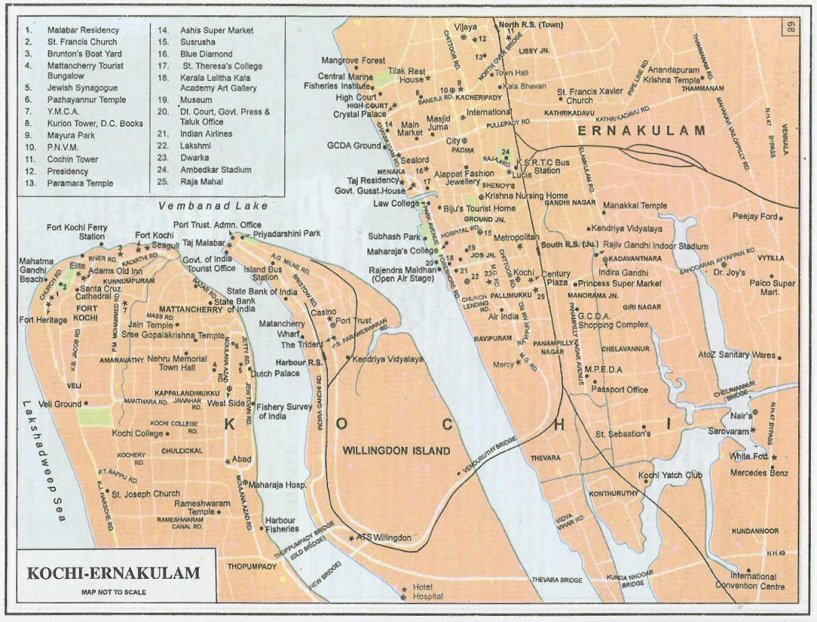

Figure1: Kochi in India

Figure 2: Map of Kochi (Source: indiamike.com)

We planned this walk by trying to get rid of our habits and pre-conceptions of the city by choosing a deliberately unusual route. To set up our itinerary we decided to link a major inner-city public transportation hub (Ernakulam main boat jetty) located at the edge of the central business district to a major transportation hub towards regional and interstate destinations (Vytilla mobility hub). These two destinations will soon be linked by the metro rail but at the moment the road traffic is frequently heavy and we chose an alternate street plan that allowed us to cross more quiet areas. The route to cover is approximately 6.2km long which is about 1 hour and 16 minutes walking distance. We deliberately chose a dry day during the monsoon season to avoid a very unpleasant experience.

The synthesis of this experiment is divided in two sections: a narrative part giving a description of our progression through the streets of Kochi. This part is divided into sections every time we shifted direction. The second part is dedicated to analyzing the main constraints that pedestrians can face in Kochi and more largely in India.

03:35pm – Start

Ernakulam Boat Jetty

Our starting point was the main Ferry Pier where a large crowd of commuters from Kochi’s Western island board and disembark every day, they continue their journey by foot, auto rickshaw or bus. At this time in the afternoon the place is not very crowded. The place is paved, pedestrians and some rare vehicles are sharing the way, the auto rickshaws are waiting for passengers. The buses on the stand are idling and their movement is not an obstacle. A new bus stand has been erected recently. As we tried to cross the road, there was no pedestrian crossing and this crossing is in fact prohibited by the police who blocked the median of the road to ban U-turns.

Figure 3: The ferry terminal ((c) Roman Ville-Glasauer)

Park Avenue Road

We turned South on Park Avenue, waiting to find a safe place to cross this road. The traffic was busy and seems difficult to cross. The footpath is discontinuous with broken tiles and it frequently leads straight into dirty puddles. Some majestic trees are providing shade but also blocking the way for pedestrians as they are implanted right on the footpath. We finally found a pedestrian crossing but the drivers seemed not to pay any attention to our presence and we had to look in their eyes to make sure they will stop. The public bus was the first vehicle to stop for us. On the other side of the road street vendors have installed their stands on the footpath and we had to walk on the road, the footpath is smaller than before (50cm) and the levels are varying.

Figure 4: A pond on Park Avenue ((c) Roman Ville Glasauer)

Hospital Road

As we headed West on Hospital road the footpath becomes very narrow, being only reduced to the cover of the side drain. Vehicles were speeding and we had to walk on the road as the footpath is too narrow for two people to walk side by side. The street is well shaded by trees. Some graffiti have been painted on the wall of the college by students and artists making this stretch a little livelier. An auto rickshaw stand was installed on the footpath making it completely inaccessible. Some private vehicles were also parked on the left side of the road. An organized bike parking is also provided, also on the footpath. We crossed the road to stay on the right side where the footpath is accessible. We reached a shop that has chosen to design its setback with a large footpath and has no fences between public and private space, this is a rare find! The following 200 meters we had to use a footpath with constantly changing levels and cars occupying the footpaths.

Figure 5: Concrete slabs as footpath ((c) Roman Ville-Glasauer)

KPCC Junction

We finally reached KPCC junction on MG Road which is the commercial center of Kochi, at the moment the metro construction works have damaged the footpaths and the road surfacing thereby the walking experience is substantially less pleasant then what would be expected on this street. The pedestrian crossing is completely faded and the traffic signal has no interface for pedestrians, we had to guess out which phase was less dangerous for us to cross the busy intersection.

MG Road

The footpath is constituted of the rain water drainage canal with concrete slabs on top, similar to many other roads of Kochi. Some of the slabs are broken and some are removed, it is already dangerous but at night or under heavy rain this is a deadly trap. We were walking in front of jewelry shops selling expensive goods but none of them seems to be concerned by the outlook of the public space just in front. Some drain cleaning works have been done and the cleaning waste is left on the footpath which is utterly disgusting and has encouraged more people to dump waste on the same place. It is impossible to walk here and we have to step on the road. We then reached a section where the car parks have been planned properly and the footpath is perfectly functional.

Figure 6: Dumpster on sidewalk ((c) Roman Ville-Glasauer)

Figure 7: Organized on-street parking on MG Road ((c) Roman Ville-Glasauer)

Jos Junction

We reached this junction just before leaving MG Road, here also the metro works are going on and it feels like a war scene, everything is broken and no fences have been set up, we walked through the remains. An electric transformer has been installed on the footpath taking all the space at the corner.

Chittoor Road (South Junction)

This is a very busy junction and a pedestrian crossing would have been much appreciated but we had to go 100 meters North to find the first one.

South Railway Station Road

This road is the main pedestrian access to the main train station of Kochi, the footpaths are extensively used here. At some places people sleep on the footpath as it is the cleanest place around. There are a lot of street vendors and some of them are blocking the way, they propose all sorts of items and foods that might be useful for busy passengers. The footpath is very high here making some buildings difficult to access. Some parts have slopes that would make access for roll chairs possible! We then witnessed an accident of a motorbike slipping on that same slope. Just before reaching the railway station the footpath becomes unusable due to a traffic police kiosk installed in the middle of the way.

Figure 8: High footfall and street vendors at South Railway Station ((c) Roman Ville-Glasauer)

South Railway Station

We chose to cross the railway tracks at the train station as it is the only way that has been specifically designed with a bridge for pedestrians to cross the tracks. The other options are: making use of the road bridge (700m distance both ways) with heavy traffic or crossing the tracks at grade which is not only dangerous but also illegal, this is how most Indians cross the railway tracks. To access the foot over bridge we had to pay ten rupees to access the platforms. The landing of the footbridge on the other side is not planned and we had to go through muddy water and grass to reach the road.

Purushu Menon Road

We then reached a semi pedestrian street (paved with interlocking concrete blocks), the vehicles where driving slower but it was still a confrontation.

Bridge over Perandoor Canal

To cross the Perandoor Canal, a new bridge was built in 2014, however the builders didn’t include any footpath on the side of this narrow bridge which makes it really unsafe to walk on.

Warehouse Road

As we were walking on a neatly maintained footpath we passed in front of the Kadavanthra Market. The smell coming from the market makes it difficult to walk in front of it. Some waste from the market is dumped on the road side. The footpath ends and we walked through an empty truck parking lot, the area is completely muddy and stray dogs sleep nearby. We preferred to walk on the road.

Figure 9: Mud and garbage as a sidewalk ((c) Roman Ville-Glasauer)

Gandhinagar Road

There is absolutely no footpath on this street but luckily we were assisted by a policeman to manage to cross the intersection. The next street is a very narrow street but with a strangely wide footpath (about 5m), the footpath is in fact the cover of a very large drain. At the next intersection the footpath disappears under plants and advertising boards.

Kaloor-Kadavanthara Road

An auto rickshaw suspecting that we shouldn’t be walking proposes to take us aboard. The only way to stay safe is to walk on the kerb as plants have eaten up the pedestrian space. At the junction there is no safe crossing but the road is paved with interlocking blocks which helps slowing down the traffic and we managed to cross.

Subhash Chandra Bose Road

We reached the beginning of this street which is mainly used to serve the surrounding residential areas. Advertisement boards are placed on the side with less clearance from the ground blocking the way. The footpath is nonexistent and replaced by white stripes. This is mainly used as a large car and bus parking lot with no way to get around and we had to walk on the road. The traffic is very heavy and fast and it was a very unsafe and unpleasant experience.

Figure 10: No sidewalk and illegal parking ((c) Roman Ville-Glasauer)

Trees and plants are planted on what should be the footpath making it unusable however, they provide a much appreciated shading for the cars parked on the side. When no cars are parked, the space is used by street vendors to set up their stall. A car nearly hits us as we try to cross the road at an intersection. Some drain cleaning waste was dumped on the side as drain works have been carried but nobody came to collect the waste.

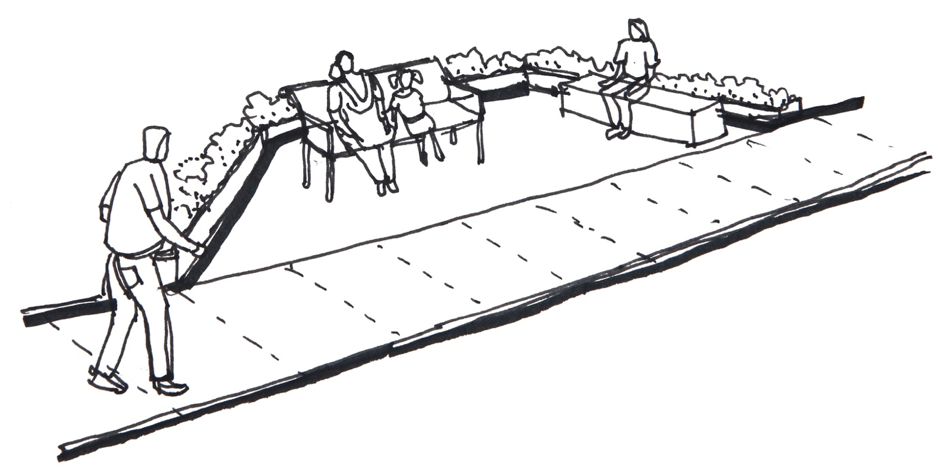

A road curve over the canal is equipped with a wide footpath, benches, a swing and sitting on the bridge’s parapet, the place is crowded every evening as this is one of the only squares of this neighborhood. We then reached a section that is more “urban”, more densely commercial and populated. There is a footpath but it is mainly impracticable because it is constantly changing level and we had to climb up to 40 cm. We chose the road again.

NH47 Underpass

As we approached from this major highway crossing the city we had no other choice but to use the underpass. It was planned only for cars and there is no space left for pedestrians, the width is very narrow and allows one car to cross each way. We had to walk in the middle of the road and be very confident that no one would try to run us over.

Figure 11: Narrow underpass ((c) Roman Ville-Glasauer)

RSAC Road

This is a neatly maintained semi-pedestrian road, paved with interlocking blocks passing through a very residential area. Unfortunately for the residents, the design of Vytilla junction (800m south) forces drivers coming from the East to cross this area to get to the city center and it turns into a traffic jam in the evening. Cars were honking to make us walk faster….

Figure 12: RSAC Road, semi-pedestrian road ((c) Roman Ville-Glasauer)

Vytilla Mobility Hub

We reached our final destination, the Vytilla mobility hub, which is the most appealing transport hub of Kochi. The place is surrounded by nature and the waiting area is shaded and well ventilated. Buses are speeding inside the hub as the space is vast but after all this heavy traffic it is very easy to cross here.

05:20pm – End

What makes it so difficult to walk on India’s streets

Challenges and negotiations

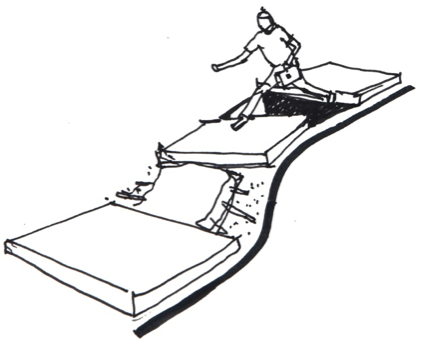

Confused sidewalks

As we could experience during our walk, only a few streets are equipped with sidewalks and even when they are provided, walking on them isn’t always possible due to very poor conception. Pedestrians have to face various natural and artificial obstacles that make their progression slower and more difficult. They can be present or absent, narrow, ill-maintained and at times not used for functions it is designated for.

(c) Bella Ullas

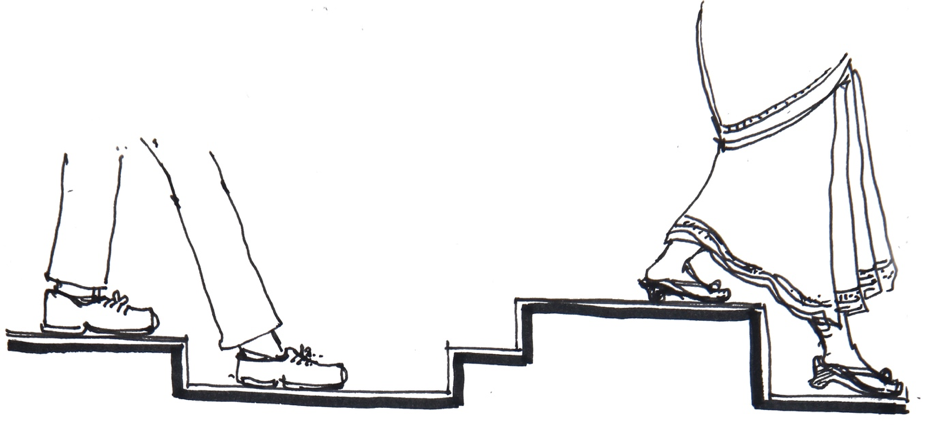

Ups and downs

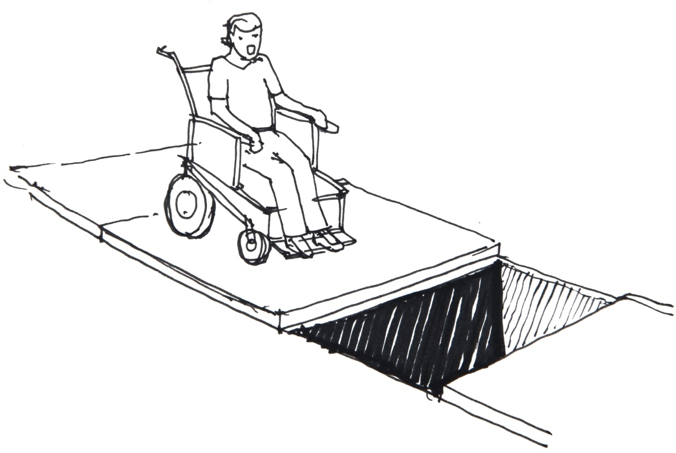

The journey for a pedestrian is rickety due to innumerous discontinuities in the pedestrian infrastructure. Most of the changes in levels are left untreated to make the sidewalk/pedestrian infrastructure continuous. The levels vary (between 10 to 45 cm), making them inaccessible to various categories of users: women with constraining clothes (sarees), elderly people, small children, disabled people, etc.

(c) Bella Ullas

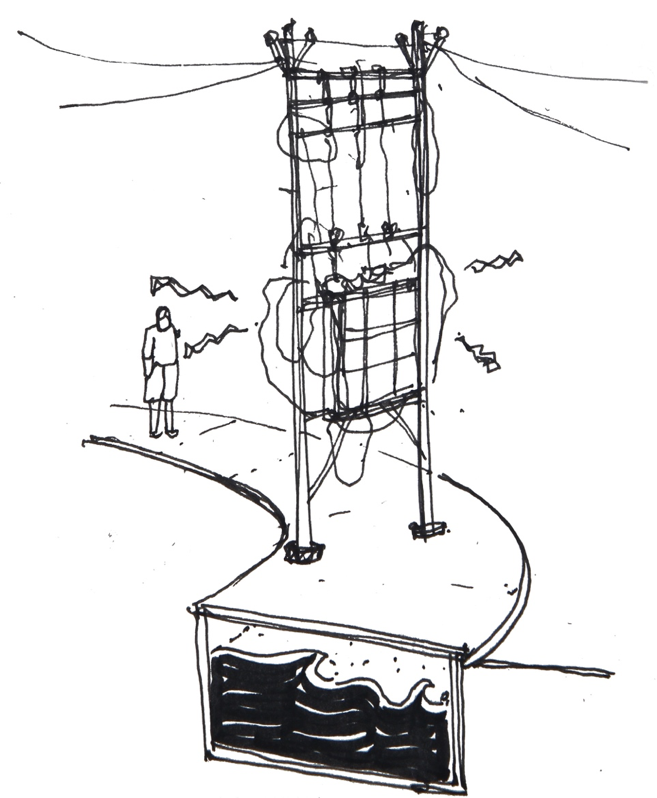

Out of sync

Streets are also a major carrier of urban service infrastructure. And lack of coordination in design between services and transportation have resulted in constant digging, repairing degrading the infrastructure. Electrical equipment such as transformers and poles are placed on the sidewalks, blocking the way for pedestrians.

(c) Bella Ullas

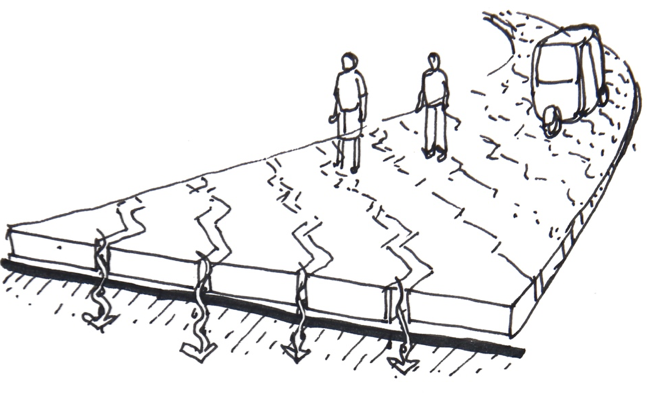

Most of the sidewalks are built on top of drainage canals that evacuate the heavy monsoon rains. The dimensions of those canals are not calculated for pedestrians that will walk on top of them but for the water flow that they will channel. Thereby the dimensions vary and some sidewalks are very narrow where others are extremely wide.

Universal accessibility

Complete negligence to universal accessibility in planning can be witnessed. This means that streets are limited to different spectrums of users and it is quite unusual to find a person with special mobility needs on Indian streets. No speck of tactile paving is to be found.

(c) Bella Ullas

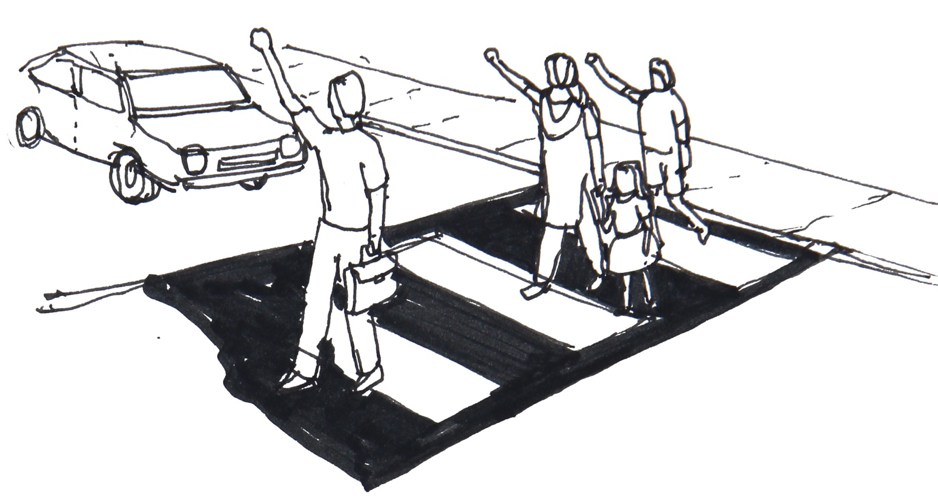

Priority

Road traffic in India is regulated according to vehicle size. As streets are not properly delimitated and there are only a few traffic lights, drivers try to find a way through the congested streets at any cost, stopping is not an option. In this context pedestrians and cyclists are at the lowest rank on the scale of what makes a driver decelerate or stop. A permanent attention is required to avoid being hit by moving vehicles or getting hurt due to breaks of the sidewalk. Nearly half of fatal accidents in Delhi involve pedestrians (NUTP, 2009). And motorists are provided with the luxury of ‘free left turns’ in most of the intersections, restraining pedestrians due to increased difficulty in crossing the intersection and lack of safety.

There is also lack of strong legal binding for pedestrians. And the presence of legislation also does not improve the situation as the law may not be properly enforced, which is clearly evident from the sidewalks and no parking zones stocked with cars, causing pedestrians to detour through the dangerous roads.

(c) Bella Ullas

Walking is exhausting

Insecure connections

Crossing the road requires confidence in one’s talent to persuade heavy vehicles drivers to stop or slow down. At major intersections, the traffic lights don’t include a separate signal for pedestrians to cross and it might be difficult to decide which one is the most favorable. Drivers are not into the habit of responding positively to pedestrian crossing marking which leads to prolonged waiting time for the latter for an opportunity to cross the road. There are places where the pedestrian crossing markings have faded.

As the police forbids U-turns on most roads by blocking the median with barricades, pedestrians have few places left to cross the roads. This attitude of the police can be explained by the presence of auto rickshaws which are in a constant need to make U-turn to pick up passengers.

(c) Bella Ullas

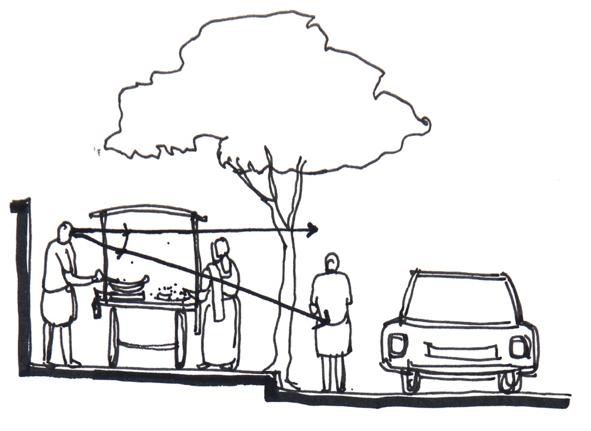

Eyes on street

Over fifty years ago, urban activist, writer and journalist Jane Jacobs developed the concept of “eyes on the street”. It focuses on safety in public spaces induced through natural surveillance obtained from various activities on street. Indian streets are active due to various informal activities like street vending which helps the street to remain active and enhances the experience of a pedestrian. Whilst most of the street vending activities are effectively providing eyes on the streets, some vendors are improperly placed and block the way on the sidewalks.

(c) Bella Ullas

Unattractive spaces

Pedestrians need infrastructures that are not directly related to the act of walking such as benches, parks, public toilets, etc. Many cities have installed urban furniture to increase footfall. In some rare exceptions these items are not present on the streets of India and there no option to rest in the public space, the only option is on private compounds. Many leading or high-end commercial establishments in the city are least bothered about the quality of space right outside the entrance. They in turn become dead spaces affecting the image of the public space.

In addition, the parks, that provide a relaxing experience to cross some parts of the city have very restricted opening times lessening the possibilities for pedestrians to rely on them as a resting space or use them as dedicated pedestrian corridors. And even when it is present, it can be not properly maintained and people lose respect for it, making it unattractive.

(c) Bella Ullas

Quality of surfaces

The surfaces which pedestrians use must be sturdy, anti-slippery, wear resistant and pleasing to the eye for safe journey of pedestrians. Nowadays, few residential streets have been treated with concrete interlocking blocks, which gives it a feel of shared space helping to reduce the speed of motorized traffic.

To provide an easy access to the drains, the sidewalks are not closed and paved, with manholes at a regular distance as international standards but closed with concrete slabs on top. As these canals also host other utilities such as water canalizations, electricity, internet cables and others, the slabs are constantly opened and left open by various private and public agencies. This leaves empty holes which can be deadly during monsoon when the streets are flooded.

(c) Bella Ullas

This is more generally due to a lack of planning and standardization, public agencies build what costs them less and accordingly to usage. In the long term this strategy is less effective and might end up costing more as the slabs must constantly be replaced, the ducts have to be cleaned more frequently, the cables are subject to rupture as they are open to sight.

In Bangalore there is an initiative called “Tender SURE” to create a masterplan for standardized sidewalks with proper pavement, manholes, railings for the cables and a regular width. This is currently being extended to the major streets in the city center and might lead to create a norm for sidewalks in India, Chennai and Hyderabad will implement this project too.

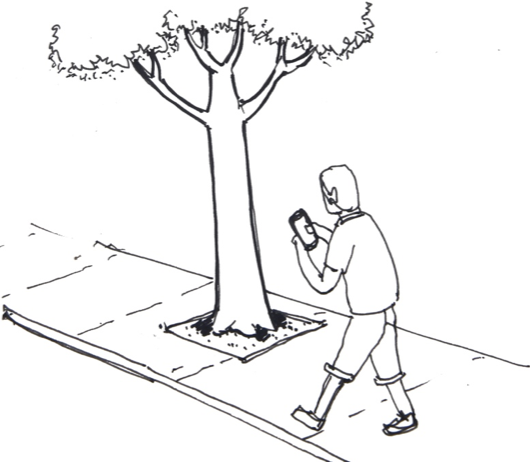

Anti-signage

Most Indian cities lack designed standard signage. It helps in easying navigation through the city and it eases the journey of pedestrians. Few initiatives are done by Kochi Metro Rail Limited during metro construction to improve the legibility of the city. There are also instances were the signage is placed in the middle of the sidewalk or does not have enough clearance from the ground, anyone can bang its head on them.

(c) Bella Ullas

Disrespect environment

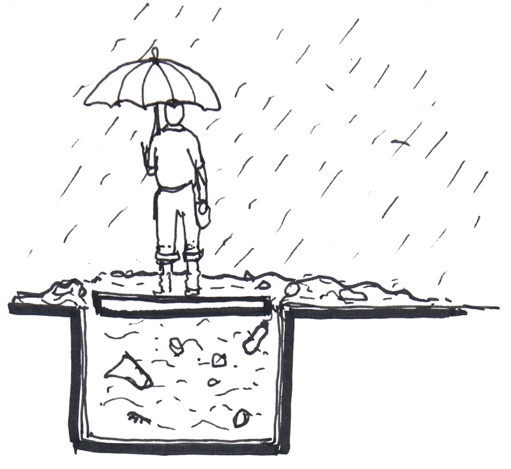

Climate resilience

India has always been a warm country but with growing urbanization and the loss of natural green surfaces in the city centers, the cities are becoming “heat islands” (The Economist, 2016). While car drivers can turn on the air conditioning, walking is only more difficult in the heat. Most of the roads in India are covered with dust as the soil is dry and roads are not systematically asphalted. Dust can agglomerate on the skin, hair and eyes and make the progression very unpleasant for longer distances.

(c) Bella Ullas

The city is not designed to withstand the water flows of heavy monsoon rains leading to “ponds” instead of sidewalks. Storm water drains, normally placed underneath sidewalks overflow, along with other debris leading to unhygienic situations. And when they dry, the debris remain untreated in the public space. Surface treatments which allows water percolation are still distant dreams.

Streets can be dirty and ugly

As waste management is a failure in most Indian cities and people are still accustomed to throw their garbage on the ground (also from moving vehicles), there is filth lying on the ground and on the sidewalk.

Waste in India is manly wet waste and the stench is important. It is difficult to keep the shoes and clothes clean at some locations. Pleasant streetscape can increase the experience of pedestrians and commute on longer distances, on the other hand, Indian streetscapes are damaged by the ugliness of cheap concrete infrastructures (flyovers among others), hanging electric wires, rests of posters and bills on the walls…

(c) Bella Ullas

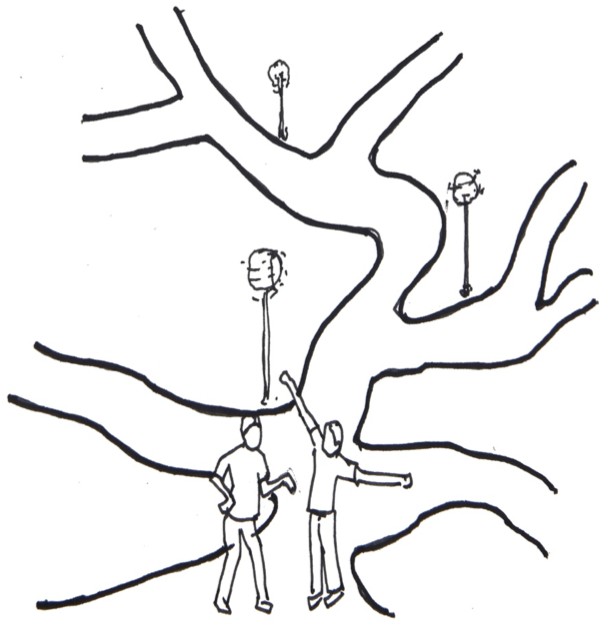

Vegetation

To provide shade to users, many streets are planted with large trees which is quite pleasant to everyone during hot days. But unfortunately, many of these trees are planted in the middle of the sidewalk or the sidewalk being constructed around it. Also due to negligence, a lot of sidewalks are overgrown with shrubbery, making it unable to use them.

(c) Bella Ullas

Blaring horns

The general noise level is very high due to the constant honking by drivers and the buzzing of two wheelers, which adds to the fatigue.

(c) Bella Ullas

There is no straight way to your destination!

Most of Indian cities (exception made of some colonial leftovers) are grew in an unplanned manner. In Kochi, the road network has developed organically based on the needs of users, and as a result many streets have dead ends (UMTC, 2016). This significantly increases the distance for road users and it is particularly inconvenient for pedestrians who face a proportionally higher distance augmentation of their trips. With the increase of motor vehicle utilization in the country, Indian cities had to deal with the problem of permanent traffic jams. Their response was to build elevated roads and flyovers which visually and physically disconnect neighborhoods.