Governance of urban mobility in Greater Abidjan: AMUGA’s mandate

Through Ordinance no. 2019-99 of 30 January 2019 amending the 2014 Loi d’Orientation du Transport Intérieur (LOTI), the State of Côte d’Ivoire has created the Greater Abidjan Urban Mobility Authority (AMUGA). The establishment of this authority is part of a more global process of decentralising the governance of urban transport that has already been underway for several decades in formerly industrialised countries, and more recently in southern countries, particularly in Africa. While structures of this type are now spreading across the continent, AMUGA is gradually establishing itself as a central authority in the governance of transport in Côte d’Ivoire, in a relatively original way that deserves to be emphasised and that is likely to inspire other metropolises on an international scale.

Creating a local authority to tackle the urban transport crisis in Abidjan

Following the economic crisis of the 1980s in Côte d’Ivoire, the country’s economic capital saw its urban transport offer marked by the very rapid development of small-scale transport services (minibuses “gbakas”, collective taxis “wôrô-wôrôs” or “warren”), compensating for the lack of structured transport provided by the buses and boat-buses of SOTRA (Société des Transports Abidjanais), which has a public service delegation agreement with the State[1]. At the same time as the different modes of transport – and consequently the modal split – have evolved, the city has seen a deterioration in traffic conditions due to population growth combined with urban sprawl, leading to increased congestion, road insecurity and air pollution. At the last census in 2021, the city had a population of 5.6 million.

It was in this local context, and more generally as part of the Transport Sector Structural Adjustment Programme (CI-PAST) promoted by the World Bank, that the Government decided in 1998 to carry out a reform of the land transport sector in Côte d’Ivoire, accompanied by a number of measures aimed at improving urban transport in Abidjan. Following these recommendations, in 2000 the Government put in place a new institutional and regulatory framework for land transport, governed by Ordinance no. 200-67 of 9 February 2000, setting out the fundamental principles of the land transport system. This new framework led to the creation of the Agence des Transports Urbains (AGETU), responsible for managing and organising urban transport within the Abidjan Urban Transport Area (PTU), which was created for this purpose and extended to the surrounding communes of Anyama to the north, Bingerville and Grand-Bassam to the east, and Dabou, Songon and Jacqueville to the west.

In terms of urban transport governance in Abidjan, AGETU’s authority was quickly challenged by the local authorities. Although they initially welcomed AGETU’s creation and supported its objectives, Abidjan’s local authorities showed a certain hostility towards it, believing that it was taking over too much of their urban transport prerogatives. As a result, AGETU was dissolved on 6 August 2014. Another argument put forward to better understand the decision to dissolve this institution concerns the lack of financial resources to enable AGETU to function effectively. Although the texts (ordinance and decree) specified the sources of funding available, the institutional changes and political instability of the period (overthrow of Henri Konan Bédié in 1999 by Robert Guéï, then of the latter by Laurent Gbagbo in 2000), and also the resistance put up by the local authorities for whom the transfer of resources to AGETU entailed a loss of revenue, explain the difficulties in mobilising the necessary funds. As a result, during AGETU’s brief existence, it was only able to maintain itself precariously thanks to State subsidies, whereas it was planned that its own resources would ensure a balanced budget from the outset.

Governance of urban mobility in Abidjan: asserting the role of a metropolitan authority

In December 2013, a number of reforms enshrined the change of strategy regarding the regulation of transport in Côte d’Ivoire. A new regulatory framework was created around the Loi d’Orientation du Transport Intérieur (LOTI)[2], which now governs the transport sector in Côte d’Ivoire. Subsequently, a general scoping study was commissioned by the Ivorian government in 2018 to analyse and define the institutional, operational and financial arrangements for setting up an Urban Mobility Organising Authority in Greater Abidjan. The Loi d’Orientation du Transport Intérieur (LOTI) is thus amended by Ordinance No. 2019-99 of 30 January 2019, establishing a new governance framework for urban mobility. Article 9 bis of the amended LOTI creates both AMUGA and ARTI – Autorité de Régulation du Transport Intérieur.

The Ivorian government’s mobility governance strategy is accompanied by the introduction of a new transport system in line with the framework set out by the Greater Abidjan Master Plan (SDUGA) in 2015[3] (the planning horizon for which has been extended to 2040) and the efficient implementation of the various planned projects. Here again, the concept of “Greater Abidjan” is not new, as it was already mentioned in the 1990s as part of the preparation of the Town Planning Master Plan for Greater Abidjan up to 2030.

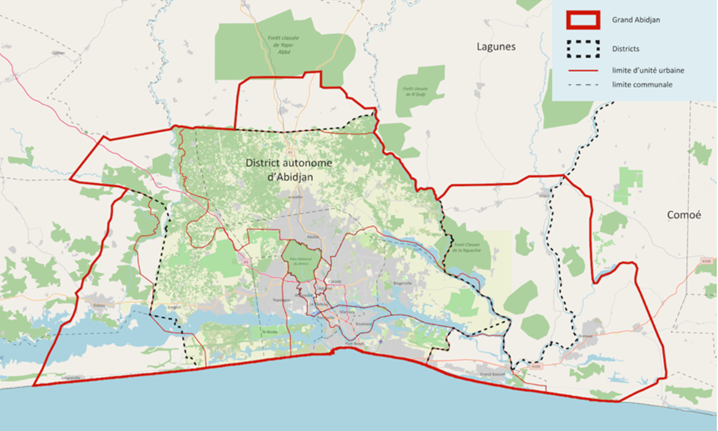

In this context, the SDUGA establishes the scope of action and competence of the new Urban Mobility Authority in Greater Abidjan, including the Autonomous District of Abidjan, made up of 13 communes, and the 6 outlying communes of Alépé, Azaguié, Dabou, Grand-Bassam, Bonoua and Jacqueville. This perimeter therefore enables AMUGA to act on a metropolitan scale and in an area that is not so much determined by an administrative division as by a functional logic, taking into account the daily travel patterns of the people of Abidjan.

AMUGA, unlike its predecessor AGETU, has been set up as an Independent Administrative Authority (AAI) with legal personality and financial autonomy. Its remit is to organise and coordinate the various modes of transport and establish “sustainable mobility for all” in Greater Abidjan.

AMUGA’s challenges in relation to the arrival of new transport services in Abidjan

In the wake of AGETU’s experience and in a context of fragmented competencies in urban mobility, the implementation of several urban transport projects represents a significant challenge for AMUGA in its early days.

In fact, several capacity-building transport modes are currently being planned, namely Line 1 of the Abidjan metro scheduled for completion by 2028[4], the above-mentioned east-west BRT line by 2026, and a second BRT line on Boulevard Latrille by 2025. In addition to planning these projects, the aim is also to integrate existing transport networks, in particular the bus services provided by SOTRA, lagoon transport and paratransit provided by gbakas and wôrô-wôrôs, while developing a strategy for non-motorised modes of transport.

Shortly after its creation, AMUGA was given the dual task of understanding the main mobility issues in Abidjan in the short and medium term, while ensuring the coordination of capacity-building projects and integration with existing services.

In addition to providing assistance to project owners, AMUGA is establishing its authority and action in the local urban transport landscape. The Authority is responsible for revising the Société des Transports Abidjanais (SOTRA) concession agreement[6], which was tacitly renewed in 2013 after being renewed in 1998 for a period of fifteen years. AMUGA is also piloting a review of the 25-year agreements signed in 2016 by the lagoon transport operators CITRANS and STL, in order to adapt them to operating conditions and the new challenges posed by the revitalisation of lagoon transport. In addition, one of AMUGA’s first initiatives was to develop infrastructure for small-scale transport operators. For example, AMUGA has identified stop-off points, drop-off points and parking areas with the participation of the local authorities, and has begun work to improve traffic flow for paratransit operators, wôrô-wôrôs and gbakas. AMUGA’s action on small-scale transport can be seen as exemplary, as a large proportion of these services, particularly wôrô-wôrôs, are in theory regulated at local level by the communes – unlike the major capacity projects – and do not rely on external funding. This gives greater flexibility in terms of the actions to be taken, and is consistent with AMUGA’s mandate. In addition, the professionalisation and integration of small-scale transport is a sine qua non for the success of capacity-building transport projects and the creation of intermodality on a metropolitan scale.

In anticipation of the integration between existing transport services and future metro and BRT services, an Intermodality Charter has been drawn up[7] and implemented by means of a decree currently being finalised, in order to commit all transport operators in Abidjan. This action to improve and prepare for modal integration is also coupled with a review of the fare policy adapted to the scale of the metropolis. A study is currently underway on this subject, to provide AMUGA with a clear vision of the various possible scenarios and the related trade-offs. These last two projects are a reminder of the crucial role played by the Organising Authorities in coordinating and integrating transport networks, particularly as new modes of transport come on stream.

Strategies to strengthen AMUGA’s legitimacy

In the context of decentralisation and consolidation of urban mobility governance in Côte d’Ivoire, the definition of a clear mandate for the Authority and the choice of actions to be prioritised by AMUGA are essential to establish the legitimacy of the Organising Authority at the Greater Abidjan level. These decisions are also accompanied by several original initiatives led by AMUGA, which are worth highlighting in order to gain a better understanding of the room for manoeuvre and governance prospects of the Organising Authorities in the cities of the South.

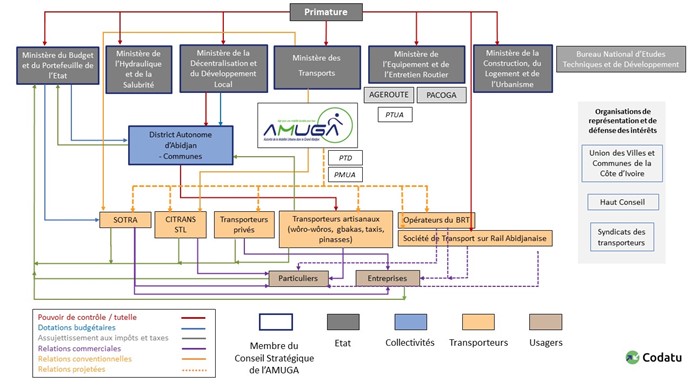

From the end of 2021, and in order to ensure that the municipalities cooperate effectively, AMUGA is setting up working groups in each of the municipalities of Greater Abidjan[8], thus identifying the focal points of the technical departments responsible for liaising with the various AMUGA projects[9]. The first task of these working groups is to help AMUGA identify all the local transport players (owners, drivers, auxiliaries, etc.). They are also expected to issue opinions on AMUGA projects, make proposals for improving the communal transport system, bring the problems of communal transport operators to their attention with a view to resolving them, and act as a channel for raising awareness and communicating on the actions of AMUGA and the Ministry of Transport. Through this initiative, AMUGA is in a position to involve communal players, while providing a specific platform for expression for paratransit operators. At a time when many Organising Authorities are struggling to establish themselves at local level, this initiative represents a judicious lever for involving local players in AMUGA’s actions. More generally, six of Greater Abidjan’s communes are represented on AMUGA’s Strategic Council[10], with seats allocated as follows:

- Ministries (9 members): Ministry of Transport (two members, one of whom chairs the Council); Ministry of the Economy and Finance; Ministry of Construction, Housing and Town Planning; Ministries of Decentralisation and Local Development; Ministry of the City[11]; Ministry of Hydraulics, Sanitation and Hygiene; Ministry of Equipment and Road Maintenance; Ministry of the Budget and State Portfolio.

- The Autonomous District of Abidjan (1 member), acting as vice-chair.

- The municipalities of Greater Abidjan (6 members), chosen by the Union des Villes et des Communes de Côte d’Ivoire – UVICOCI, for a renewable 3-year term.

One of AMUGA’s short-term objectives is to set up a Mobility Observatory for Greater Abidjan. Once again, this initiative is part of a more global trend, namely the ability of public authorities to collect and analyse mobility data (in particular to help with prevention, develop the SAEIV and support planning), and also reflects AMUGA’s desire to facilitate intermodality and integration between the different modes of transport in Abidjan. However, beyond these objectives, the establishment of an observatory also represents a strategic tool for evaluating the public policies implemented, and therefore the action taken by the Authority. AMUGA’s legitimacy is also based on a policy of transparency. To this end, the Urban Mobility Days were organised in Abidjan in November 2022, under the aegis of AMUGA. Once again, the aim of this event was twofold: on the one hand, to ensure AMUGA’s visibility in the urban transport landscape in Abidjan, and on the other, to create a platform for discussion between all the players, in order to strengthen the Authority’s coordinating role.

Conclusion

The creation of the Greater Abidjan Urban Mobility Authority is part of a process that is now well known internationally, and for some years now in sub-Saharan Africa too. Without seeking to identify a prescriptive model, the experience of this Ivorian institution enables us to identify a number of ‘best practices’ and innovative configurations that could inspire other metropolises. First and foremost, the setting up of AMUGA, in the wake of AGETU, highlights the fact that the creation of public institutions such as Mobility Organising Authorities is a lengthy process, requiring a strong political will and support at all levels. In addition, the question of the scope of the area to be covered is central, in particular to take into account the actual daily mobility of city dwellers, and to go beyond the sometimes inadequate boundaries of administrative boundaries. On this point, consistency between the level at which AMUGA and the Schéma d’Urbanisme operate is a guarantee of a better match between the practices of city dwellers, mobility planning and urban planning. Finally, including the municipalities in AMUGA’s governance also represents an innovative way of consolidating the institution’s authority at the metropolitan level, while ensuring that it operates democratically at local level. At a time when decentralisation is often not complete in many areas of the South, this local base is proving to be relatively original and all the more valuable. After just three years in existence, a great deal has been achieved, but there are still a number of challenges to be met if AMUGA is to succeed in reorienting urban mobility in Greater Abidjan and establish itself as a key player in the field. The main challenges identified to date are of various kinds:

- The creation of the Greater Abidjan Urban Mobility Authority is part of a process that is now well known internationally, and for some years now in sub-Saharan Africa too. Without seeking to identify a prescriptive model, the experience of this Ivorian institution enables us to identify a number of ‘best practices’ and innovative configurations that could inspire other metropolises. First and foremost, the setting up of AMUGA, in the wake of AGETU, highlights the fact that the creation of public institutions such as Mobility Organising Authorities is a lengthy process, requiring a strong political will and support at all levels. In addition, the question of the scope of the area to be covered is central, in particular to take into account the actual daily mobility of city dwellers, and to go beyond the sometimes inadequate boundaries of administrative boundaries. On this point, consistency between the level at which AMUGA and the Schéma d’Urbanisme operate is a guarantee of a better match between the practices of city dwellers, mobility planning and urban planning. Finally, including the municipalities in AMUGA’s governance also represents an innovative way of consolidating the institution’s authority at the metropolitan level, while ensuring that it operates democratically at local level. At a time when decentralisation is often not complete in many areas of the South, this local base is proving to be relatively original and all the more valuable. After just three years in existence, a great deal has been achieved, but there are still a number of challenges to be met if AMUGA is to succeed in reorienting urban mobility in Greater Abidjan and establish itself as a key player in the field. The main challenges identified to date are of various kinds:

- the ability to propose and secure sustainable funding for the institution that matches its ambitions,

- the operational implementation of its role as contracting authority for urban transport operators, and the implementation of an ambitious policy in terms of intermodality and the planning of all forms of mobility throughout its territory,

- the need to control the time-consuming processes of consultation and validation of the technical options adopted.porting AMUGA in meeting these challenges and consolidating the foundations of sustainable urban mobility in Abidjan.

CODATU, as a technical cooperation partner financed by AFD, is committed to supporting AMUGA in meeting these challenges and consolidating the foundations of sustainable urban mobility in Abidjan.

[1] The Ivorian State owns 60.13% of SOTRA, 39.80% is held by IVECO/IRISBUS and 0.07% by the Autonomous District of Abidjan.

[2] Phase 1 of the SDUGA 2015 was carried out using data collected in 2013. A Phase 2 of implementation and revision of Phase 1 is underway, carried out by the RECS and Urbaplan offices with funding from JICA: https://news.abidjan.net/articles/707511/cote-divoire-la-2e-phase-de-loperationnalisation-du-schema-directeur-du-grand-abidjan-dans-sa-phase-active-ministere

[3] Law no. 2014-812 of 16 December 2014 on the Orientation of Inland Transport (LOTI), amended in 2018 and 2019 (ordinances no. 2018-09 of 10 January 2018 and no. 2019-99 of 30 January 2019) with the creation of AMUGA and ARTI. It is quite similar to the LOTI law adopted in France in 1982.

[4] Delivery officially scheduled for 2025.

[5] The Abidjan Urban Transport Project (PTUA) is the coordination unit for the construction of the 4th Adjamé-Attécoubé bridge in particular; The Abidjan Sustainable Transport Project (PTD) is the unit for the implementation of a biofuel production plant and the BRT project on boulevard Latrille; The Abidjan Urban Mobility Project (PMUA) is the coordination unit for the East-West BRT project.

[6] SOTRA is a semi-public company that operates the largest bus network in West Africa. It operates around 1,500 buses (2021) and 10 water buses (2018). It currently provides daily transport for around 1,200,000 passengers on a network of around 1,785 km.

[7]Developed by Setec, delivered in May 2022.

[10] The 6 municipalities represented on the AMUGA Strategic Council are Attécoubé, Cocody, Marcory, Plateau, Treichville and Yopougon.

[11] This ministry was abolished as its remit overlapped with that of the Ministry of Construction, Housing and Town Plannin